Holy Ghost Girl Excerpt

Chapter One

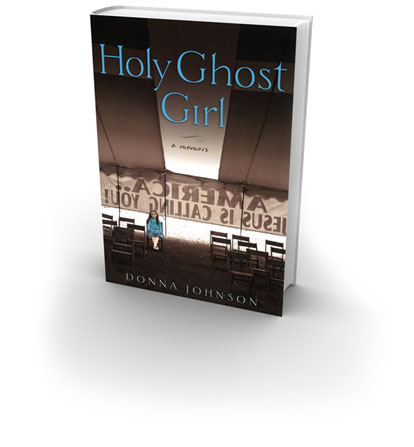

The tent waited for us, her canvas wings hovering over a field of stubble that sprouted rusty cans, A&P flyers, bits of glass bottles, and the rolling tatter of trash that migrated through town to settle in an empty lot just beyond the city limits. At dusk, the refuse receded, leaving only the tent, lighted from within, a long golden glow stretched out against a darkening sky. She gathered and sheltered us from a world that told us we were too poor, too white trash, too black, too uneducated, too much of everything that didn't matter and not enough of anything that did. Society, or at least the respectable chunk of it, saw the tent and those of us who traveled with it as a freak show, a rolling asylum that hit town and stirred the local Holy Rollers, along with a few Baptists, Methodists, and even a Presbyterian or two, into a frenzy. Brother Terrell reveled in that characterization.

"I know they's people call me David Nut Terrell. I'm not ashamed of it." He bounced up and down the forty- foot- long platform with the pop and spring of a pogo stick. "I'm crazy for Jesus, crazy for the Lord." The crowd was on its feet, pogoing with him.

The tent went up in all kinds of weather, but in my memory it's always the hottest day of summer when the canvas rises. A cloud of dust hangs over the grounds, stirred by the coming and going of the twenty to thirty people it took to raise the canvas. Local churches sent out volunteers, but most of the work was done by families who followed Brother Terrell from town to town, happy to do the Lord's work for little more than a blessing and whatever Brother Terrell could afford to pass along to them. When he had extra money, they shared in it. He had a reputation as a generous man who "pinched the buffalo off every nickel" that passed through his hands. He employed only two to four "professional" tent men, a fraction of the number employed by organizations of a similar size. The number of employees remained the same over the years even as the size of the tents grew larger. "World's largest tent. World smallest tent crew," was the joke.

The air smelled of grease and sweat. Men dressed in long pants and long- sleeved shirts (the Lord's dress code) ran back and forth, calling to one another over the gear grind of the eighteen- wheeler as it pulled one of seven thirty- foot center poles into the air. I held my breath as the men wrestled the poles into place, praying that a pole didn't fall and knock a couple of men straight to glory, but making sure I didn't miss it if it did. With a couple of center poles secured, the men broke for lunch, mopping their faces with red or blue bandanas or an already soaked shirtsleeve. Pam and I brought out the trays of bologna sandwiches our mothers had made and walked among them passing out the food. I tried not to wrinkle my nose at the greasy imprints their fingers made in the white bread or the sour hugs that accompanied their thank-yous.

It took three to four days to put the tent up, and the site looked different each time we visited. Some days I picked my way through red and blue poles that lay on the ground in seemingly careless arrangements, imagining them as tall slender ladies who had fainted in the heat or young girls waiting to be asked to dance. Proof that a romantic temperament can take root anywhere, because the only dancers I had seen were believers who jigged in the spirit. The men rolled out sections of canvas over the horizontal poles, attaching the cutout pieces to the base of the now- raised center poles. They laced the sections together and swarmed the flattened tent like a team of tiny tailors stitching a ball gown for a female colossus. With the sewing finished, a man was stationed at the winch attached to each of the seven center poles. Someone shouted, "Go!" and the men cranked in unison. The canvas rose around them, and when it reached waist height, crew members hunched over like gnomes, scrambled underneath, and pushed up the secondary poles. A few more cranks and the peaks billowed thirty feet in the air.

With the tent secured, the crew hung spotlights and secondary lighting from the poles, hammered together the sections of the platform, unloaded the Hammond organ, and positioned the amplifiers and speakers. The expanse of the tent posed a challenge for the sound system, so it was important that the speakers be positioned in just the right places. The tent families unloaded stacks of wooden folding chairs and arranged them in orderly sections that fanned outward from the platform. Twenty- five hundred chairs for the first night, with a thousand more stacked in the truck to be squeezed in as needed throughout the revival. Long one-by-one boards were placed between the chairs' legs to connect them and keep the rows uniform.

By seven o'clock on opening night, a dusty brown canvas and a collection of scuffed-up poles had been transformed into an ad hoc cathedral. People came from near and far. Black and white, old and young, poor and poorer. Women with creased brows and apologetic eyes as faded as their cotton dresses, clutching two and three children who looked almost as worn out as their mothers. Men, taut as fiddle strings, hunch- shouldered in overalls or someone else's discarded Sunday best, someone taller and better fed. They came to find a sense of purpose and a connection to God and one another. They came because the promises of the beatitudes were fulfilled for a few hours under the tent, and the poor were truly blessed. They came for miracles, answers, and salvation. They came to see the show.